Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) Prevention for Ultramarathon Runners: Strategies, Symptoms & Science

Planning to run long where the air gets thin? If your ultra takes you above 2,000 meters, acute mountain sickness (AMS) is a real threat—no matter how tough you are at sea level.

This guide delivers science-backed prevention, symptom checklists, smart medication use, and real strategies to keep you healthy and moving strong at altitude. Lost Pace style: clear, practical, and zero hype.

🏔️ What is Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)?

Acute Mountain Sickness is your body’s reaction to lower oxygen and pressure at high altitudes—typically above 2,000–2,500 meters (6,600–8,200 ft). It develops hours or days after ascent. While usually mild, it can progress to dangerous, even life-threatening forms like HAPE (high-altitude pulmonary edema) or HACE (cerebral edema) if ignored.

- Common in first 24–48 hours: Risk is highest after rapid ascent.

- Not just a “bad day”: AMS isn’t about grit—it’s about physiology.

- Fully preventable (most cases): With smart pacing, hydration, and awareness, you can reduce your risk to near zero.

👟 Why Ultramarathoners Should Care About AMS

- Time at risk: Ultramarathons mean longer exposure, higher cumulative stress, and more overnight symptoms than “normal” mountain hikes.

- Race pace masks warning signs: Fatigue, poor sleep, and mild confusion are “normal” in ultras—but they’re also AMS red flags.

- Medical support is limited: Remote trails, weather, and limited access mean you must self-manage and self-prevent.

- Performance is secondary: AMS means DNF or worse. Your first goal: finish safely, then chase speed.

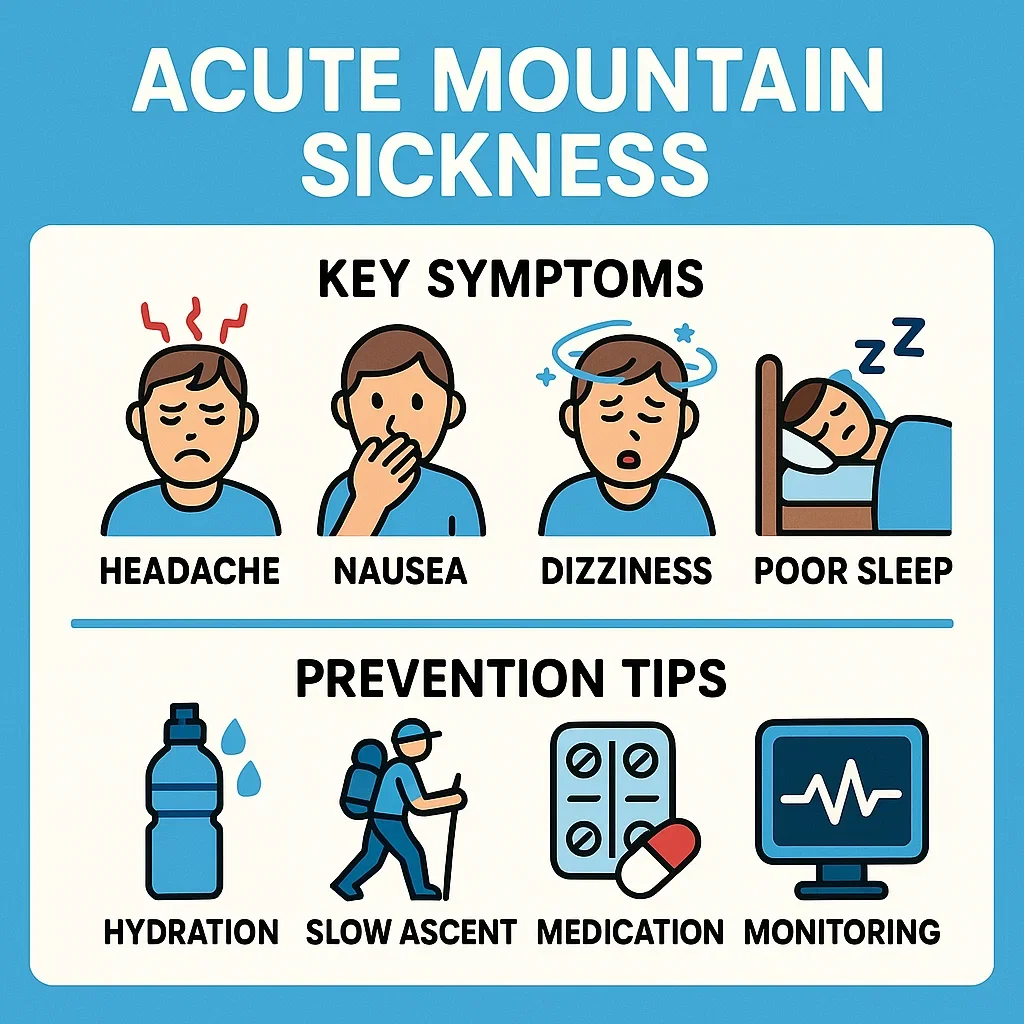

🩺 Main Symptoms of AMS (What to Watch For)

- Headache (the #1 symptom, especially if new or severe at altitude)

- Nausea or vomiting (feeling sick, trouble eating or keeping food down)

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, or feeling faint

- Poor sleep (waking up often, insomnia, restless)

- Fatigue, weakness, “heavy legs”

- Loss of appetite

- Mild confusion, trouble concentrating

⚠️ AMS Risk Factors for Runners

- Ascent above 2,500 meters in <24 hours (especially flying or driving directly to altitude)

- First exposure (no recent mountain trips)

- Pushing hard on day 1–2 (racing, running fast climbs)

- Dehydration or inadequate calorie intake

- Previous AMS episode or history of altitude illness

- Poor sleep, illness, or jet lag before race

- Ignoring symptoms due to “race focus”

🧭 How to Prevent AMS: The Essential Playbook

🧭 How to Prevent AMS: The Essential Playbook

- Ascend slowly: If possible, spend 2–3 nights at 1,800–2,500m before going higher. If not possible, avoid hard efforts for your first 24–48 hours at altitude.

- Hydrate well: Drink to thirst, but not excessively. Add electrolytes and check your urine color (aim for light yellow).

- Fuel up: Eat extra carbs and calories—energy needs rise with altitude. Don’t fast or skip meals.

- Sleep smart: Prioritize quality sleep, even if it means earplugs, a sleep mask, or a light sleeping aid (as prescribed).

- Monitor symptoms: Use a daily AMS checklist, and carry a simple pulse oximeter to watch SpO₂.

- Pace yourself: Go 10–20% slower than usual for the first two days. Your ego is not your ally at altitude.

- Rest when unsure: Any headache, dizziness, or nausea? Take a break. Don’t push “through” it, especially early.

- Never ignore danger signs: If symptoms get worse or you feel chest pain, confusion, trouble walking—descend ASAP, no excuses.

💊 Medication & Supplements: What Actually Works?

- Acetazolamide (Diamox): The gold standard for AMS prevention. Start 24–48h before ascent, continue for 2–3 days at altitude (125–250 mg twice daily; check with your doctor).

- Dexamethasone: For those who can’t take acetazolamide, or in high-risk scenarios. Prescription only; medical supervision required.

- Ibuprofen: May help with mild AMS headache, but not true prevention.

- Iron: For those with low ferritin; improves red cell adaptation, but not direct AMS protection.

- Ginkgo biloba, herbal blends: Evidence is weak and inconsistent. Don’t rely on these for real races!

- Oxygen tanks/cylinders: May help short-term at aid stations, but not a substitute for descent or medical care.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

⛰️ What’s the fastest way to acclimatize before a race?

🩸 Should I take acetazolamide before every high-altitude race?

🩺 Is it safe to “run through” mild AMS symptoms?

💧 Can dehydration trigger AMS?

🏃♂️ Are elite athletes immune to AMS?

👟 What should I do if I get AMS symptoms mid-race?

🧪 Can caffeine or alcohol worsen AMS?

🔬 Does using a pulse oximeter guarantee safety?

💊 Do herbal supplements prevent AMS?

⏱️ If I descend after AMS, how soon can I try again?

🏁 Summary & Lost Pace Final Thoughts

AMS prevention isn’t about luck or willpower—it’s about knowledge, pacing, and listening to your body in the mountains. The strongest ultrarunners know when to push, but more importantly, when to pause, hydrate, and descend if needed.

Remember: No medal or finish line is worth your long-term health. Prepare smart, monitor symptoms, and make the call that keeps you safe for many more races ahead.

About the Author

Lost Pace is an ultramarathon runner, shoe-tester and the founder of umit.net. Based year-round in Türkiye’s rugged Kaçkar Mountains, he has logged 10,000 + km of technical trail running and completed multiple 50 K–100 K ultras.

Blending mountain grit with data, Lost analyses power (CP 300 W), HRV and nutrition to craft evidence-backed training plans. He has co-written 260 + long-form guides on footwear science, recovery and endurance nutrition, and is a regular beta-tester of AI-driven coaching tools.

When he isn’t chasing PRs or testing midsoles, you’ll find him sharing peer-reviewed research in plain English to help runners train smarter, stay healthier and finish stronger.

Ultrarunner · Data geek · Vegan athlete