Ever hit that wall during a run, feeling inexplicably drained even when you thought you fueled right? Or maybe you’ve finished a race feeling dizzy, nauseous, or battling muscle cramps? Often, the hidden culprit isn’t just fatigue or poor pacing – it’s dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, silently sabotaging your performance and well-being.

We all know sweating is part of running, but do you really understand how much fluid you’re losing? Relying on generic advice like “drink 8 glasses a day” or just sipping when thirsty might not be enough, especially during intense training or in challenging conditions. The secret weapon used by elite athletes and savvy runners? Understanding their individual sweat rate.

This guide is your deep dive into the world of sweat rate. We’ll unravel the science behind why you sweat, show you exactly how to use the calculate sweat rate running formula, help you interpret your results, and crucially, teach you how to build a personalized hydration plan that can unlock new levels of performance and keep you running strong and healthy. Get ready to take control of your hydration!

II. Your Body’s Air Conditioner: The Science of Sweating While Running

Why do we even sweat? It’s not just a damp inconvenience; it’s a sophisticated biological process essential for survival during exercise.

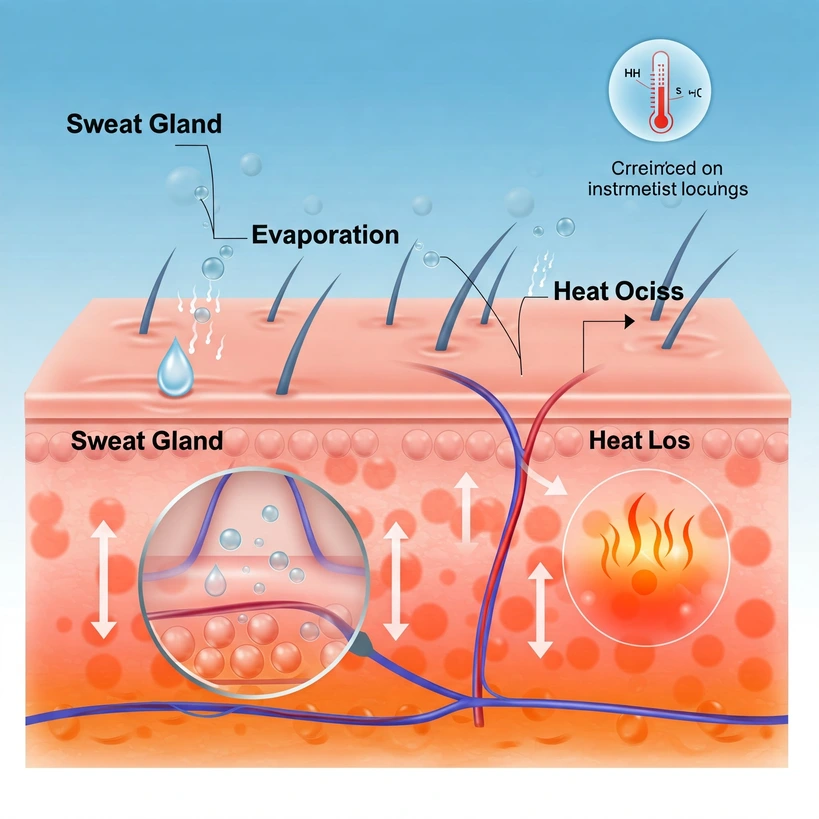

- Thermoregulation 101: Running is hard work, metabolically speaking. Your muscles generate a significant amount of heat – sometimes 10 to 20 times more than when you’re resting! If this heat builds up, your core body temperature rises, leading to performance decline and potentially dangerous conditions like heat exhaustion or heat stroke. Your body needs an effective way to cool down.

- Sweat Evaporation: The Primary Cooling Engine: While your body has a few ways to lose heat (like radiating it off your skin), the most powerful method during exercise, especially in warmer conditions, is through the evaporation of sweat. Tiny glands in your skin (eccrine sweat glands) release sweat onto the surface. As this liquid turns into vapor (evaporates), it uses heat energy from your skin, effectively cooling you down. Think of it like your body’s built-in air conditioning system. Every liter (or about 34 oz) of sweat that evaporates removes a substantial amount of heat.

- It’s Not Just Sweating, It’s Evaporation That Counts: Here’s a crucial point: cooling only happens when sweat evaporates. If the air is already thick with moisture (high humidity), sweat can’t evaporate easily. It might just drip off you, representing lost fluid without providing much cooling benefit. This is why running in high humidity often feels so much harder and riskier – your cooling system is less efficient.

- Defining Sweat Rate: Simply put, your sweat rate is the amount of fluid you lose through sweat over a specific period. It’s typically measured in liters per hour (L/hr) or fluid ounces per hour (oz/hr). Knowing this number is the first step towards understanding your individual hydration needs.

III. The Shadow of Dehydration: Impact on Performance and Health

Ignoring fluid loss isn’t just uncomfortable; it actively hinders your running and can pose health risks.

- The 2% Threshold: Sports scientists generally agree that losing more than 2% of your body weight through sweat during exercise marks the point where performance starts to decline noticeably. For a 150lb (68kg) runner, that’s just 3 lbs (1.4kg) of fluid loss.

- Performance Sabotage: Even mild dehydration can:

- Increase Cardiovascular Strain: Your blood volume decreases, making your heart work harder to pump blood (higher heart rate for the same effort).

- Raise Core Body Temperature: Reduced blood flow to the skin impairs heat dissipation.

- Increase Perceived Effort: Everything feels harder than it should.

- Impair Heat Transport: Your body struggles to move heat from working muscles to the skin.

- Health Risks: Beyond performance, significant dehydration increases the risk of:

- Heat Exhaustion (dizziness, nausea, fatigue, headache)

- Heat Stroke (a medical emergency characterized by high core temp, confusion, loss of consciousness)

- It’s Not Just Water: The Electrolyte Factor: Sweat isn’t pure water. It contains essential minerals called electrolytes, primarily sodium and chloride, along with smaller amounts of potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Losing significant amounts of sweat means losing significant electrolytes. Trying to rehydrate with plain water alone after heavy sweating can dilute the electrolytes remaining in your body, potentially leading to a dangerous condition called hyponatremia (low blood sodium).

Understanding your sweat rate helps you prevent crossing that critical 2% dehydration threshold and manage electrolyte balance.

IV. The Golden Key: The Calculate Sweat Rate Running Formula & Its Logic

Ready to unlock your personal hydration code? The most practical way to determine your sweat rate outside of a lab involves measuring changes in body mass before and after a run, adjusted for fluids consumed and urine produced. Here’s the standard calculate sweat rate running formula:

Using Metric Units (Kilograms and Liters):

Sweat Rate (L/hr) = [(Pre-Exercise Body Mass (kg) - Post-Exercise Body Mass (kg)) + Fluid Intake (L) - Urine Output (L)] / Exercise Duration (hr)

Using Imperial Units (Pounds and Fluid Ounces):

- Calculate Weight Lost (lbs): Pre-Exercise Weight (lbs) – Post-Exercise Weight (lbs)

- Convert Weight Lost to Ounces: Weight Lost (lbs) * 16 oz/lb

- Calculate Total Fluid Loss (Sweat in oz): Weight Lost (oz) + Fluid Consumed (oz) – Urine Loss (oz)

- Calculate Sweat Rate (oz/hr): Total Fluid Loss (oz) / Exercise Duration (hr)

(Note: 1 liter ≈ 33.8 fluid ounces; 1 kilogram ≈ 2.2 pounds)

The Logic Behind the Formula:

- Body Mass Change (Pre – Post): This difference primarily reflects the weight you lost, mostly through sweat, but also urine and a tiny bit through breathing.

- + Fluid Intake: You need to add back the weight of any fluids you drank during the run because this intake offset some of the weight loss.

- – Urine Output: You subtract any urine lost because this was fluid lost through a non-sweat route. We want to isolate sweat loss.

- / Exercise Duration: Dividing the total calculated sweat loss (in liters or ounces) by the time you ran (in hours) gives you the rate – how much you sweat per hour.

This calculate sweat rate running formula provides a reliable estimate of your fluid losses under specific conditions.

V. The Art of Precision: Nailing Your Sweat Rate Calculation Measurements

The accuracy of your calculated sweat rate hinges entirely on how precisely you measure each component. Garbage in, garbage out!

- 1. Body Weight (Pre- and Post-Exercise):

- The Scale: Use an accurate digital scale, preferably one measuring to within 0.1 kg or 0.2 lbs. Consistency is key – use the same scale for both measurements.

- Timing: Weigh yourself immediately before starting your run, after emptying your bladder. Weigh yourself again immediately after finishing, before drinking anything else.

- Clothing: The most accurate method is to weigh yourself nude both times. If that’s not practical, wear the exact same minimal clothing (e.g., just shorts or shorts and a sports bra) for both weigh-ins. Remember, sweat trapped in clothes adds weight and can lead to underestimating your sweat loss.

- Post-Run: Towel dry thoroughly before stepping on the scale for the post-exercise measurement. Remove excess sweat from your skin and hair.

- 2. Fluid Intake:

- Track Everything: Meticulously record all fluids consumed during the specific exercise period you’re measuring.

- Best Method: Weighing: The most precise way is to weigh your water bottles/flasks/hydration pack before you start (in grams or ounces). Weigh them again immediately after you finish. The difference is the amount you consumed. Since 1 gram of water is almost exactly 1 milliliter (and 1 fl oz ≈ 29.57 g), you can easily convert mass consumed to volume (e.g., 500g consumed ≈ 500ml = 0.5L).

- Alternatives: Using bottles with volume markings is less accurate but usable if scales aren’t available. Estimate carefully.

- No Sharing/Spitting: Don’t share fluids or just rinse your mouth and spit during the test period, as this invalidates the intake measurement.

- 3. Food Intake (The Often-Missed Correction):

- Why It Matters: Consuming gels, chews, bars, or other solid/semi-solid fuel during your run adds mass to your body. If you don’t account for this, you’ll underestimate your actual weight loss from sweat, thus underestimating your sweat rate.

- How to Account: For maximum accuracy, especially on longer runs with significant fueling, weigh your food/gels before the run and weigh any remaining portion after. Subtract the mass consumed from your calculated body mass change (or conceptually, add it to the fluid intake side, though it’s mass, not volume). While sometimes skipped in simpler calculations, rigorous protocols include this step.

- 4. Urine Output:

- Impact: Urine is fluid and mass lost, but it’s not sweat. If you urinate during the test period and don’t account for it, that weight loss will be mistakenly attributed to sweat, leading to an overestimation of your sweat rate. This error can be significant.

- Ideal Scenario: Try to avoid urinating during the test period if possible (often feasible for runs under 60-90 minutes).

- Measurement (If Necessary): If you must go, collect all urine in a lightweight, sealable container. Weigh the collected urine afterwards (a precise kitchen scale works well). Again, 1 gram of urine is approximately 1 milliliter (1g ≈ 1ml).

- Estimation Pitfalls: Estimating volume (e.g., assuming 300ml or 10-12 oz per bathroom break) is highly inaccurate and should be avoided if possible, as actual volumes vary greatly.

- 5. Exercise Duration:

- Record Accurately: Note the precise start and stop time of your run, corresponding exactly to the period between your pre- and post-exercise weigh-ins.

- Convert to Hours: Ensure your duration is in hours for the final calculation (e.g., 90 minutes = 1.5 hours; 45 minutes = 0.75 hours).

Unit Consistency and Conversions:

- Metric is Easiest: Using kilograms (kg) for mass and liters (L) or milliliters (ml) for volume is often simplest because 1 kg of weight loss closely approximates 1 L of fluid loss (1g ≈ 1ml).

- Imperial Needs Care: If using pounds (lbs) for mass and fluid ounces (fl oz) for volume, be precise with conversions:

- 1 lb ≈ 0.454 kg

- 1 kg ≈ 2.205 lbs

- 1 fl oz ≈ 0.02957 L ≈ 29.57 ml

- 1 L ≈ 33.8 fl oz

- A common field approximation: 1 lb weight loss ≈ 16 fl oz fluid loss.

- Rule: Use consistent units throughout a single calculation!

(Imagine a quick reference table here summarizing Variable, Unit, Measurement Method, Potential Errors)

VI. Step-by-Step Calculation: Putting the Formula into Practice

Let’s walk through applying the calculate sweat rate running formula with examples:

Metric Example:

- A runner weighs 70.0 kg before their run (after voiding).

- The run lasts 1 hour and 30 minutes (1.5 hours).

- During the run, they drink from a bottle that weighed 750g initially and 250g afterward.

- They did not urinate during the run.

- Their post-run weight, after toweling dry, is 68.5 kg.

- Calculate Body Mass Lost: 70.0 kg (pre) – 68.5 kg (post) = 1.5 kg

- Calculate Fluid Intake: 750g (initial bottle) – 250g (final bottle) = 500g. Convert to Liters: 500g ≈ 500ml = 0.5 L.

- Account for Urine Output: 0 L.

- Calculate Total Sweat Loss (Volume): 1.5 kg (mass lost) + 0.5 L (fluid intake) – 0 L (urine output) = 2.0 L

- Calculate Sweat Rate: 2.0 L / 1.5 hr = 1.33 L/hr

Imperial Example (with estimated urine):

- A runner weighs 155.0 lbs before a run (after voiding).

- The run lasts 2 hours.

- During the run, they drink 20 fl oz of sports drink.

- They stop once to urinate, estimating the loss at 10 fl oz.

- Their post-run weight, after toweling dry, is 151.5 lbs.

- Calculate Weight Lost (lbs): 155.0 lbs (pre) – 151.5 lbs (post) = 3.5 lbs

- Convert Weight Lost to Ounces: 3.5 lbs * 16 oz/lb = 56 oz

- Identify Fluid Consumed: 20 fl oz

- Identify Urine Loss (Estimated): 10 fl oz

- Calculate Total Fluid Loss (Sweat): 56 oz (weight lost) + 20 fl oz (fluid consumed) – 10 fl oz (urine loss) = 66 oz

- Calculate Sweat Rate: 66 oz / 2 hr = 33 oz/hr

While understanding the manual calculation is vital, several online calculators and apps (like those from Gatorade Sports Science Institute, Precision Fuel & Hydration, etc.) can automate this process once you accurately input your measurements.

VII. Beyond the Basics: Minor Factors Affecting Accuracy

The standard body mass change method is practical and generally accurate for field use. However, it’s worth knowing about two minor physiological factors that contribute to weight change but are typically ignored in this calculation:

- Respiratory Water Loss: You lose water vapor with every breath you exhale. The amount depends on how hard you’re breathing and the humidity of the air.

- Metabolic Mass Changes: Your body uses fuel (carbs, fats) and oxygen to create energy, producing carbon dioxide and water. The mass of CO2 exhaled is usually slightly less than the mass of O2 consumed, resulting in a very small net loss of body mass unrelated to sweat or urine.

In typical running scenarios, these losses are small compared to sweat loss, especially in moderate to hot conditions. Therefore, the standard formula is widely accepted for practical purposes, although it slightly overestimates true sweat loss by including these minor non-sweat losses. The biggest potential errors usually come from inaccurate weighing, inconsistent clothing, or failing to properly account for fluid/food intake and urine loss.

VIII. Why Does My Sweat Rate Change? Factors Influencing Your Fluid Loss

Your sweat rate isn’t a fixed number! It’s a dynamic response influenced by a complex interplay of who you are and the conditions you’re running in. Understanding these factors is key to interpreting your results and predicting needs.

A. Intrinsic (Individual) Factors: It’s About You

- Genetics: Like height or eye color, your sweating tendency has a genetic component. Some people are naturally “heavy sweaters” due to factors like the number or responsiveness of their sweat glands, while others lose relatively little fluid under the same conditions.

- Sex: On average, males tend to have higher sweat rates than females, even when exercising at similar relative intensities and conditions. This is often linked to typically larger body size, greater muscle mass (generating more heat), and potentially hormonal differences.

- Body Size and Composition: Larger individuals generally produce more heat at a given running speed and have a larger surface area, requiring higher sweat rates for cooling. More muscle mass also means more heat production.

- Fitness Level (Aerobic Capacity): Endurance training makes your sweating mechanism more efficient. Fitter runners often:

- Start sweating earlier (at a lower core temperature).

- Can achieve higher peak sweat rates (better cooling capacity for high intensity).

- Age: While less impactful than other factors, age can play a role, with potential differences in thermoregulation between different age groups.

B. Extrinsic (External/Situational) Factors: It’s About the Run

- Exercise Intensity: This is arguably the most powerful determinant. Run harder, generate more heat, sweat more. Simple as that.

- Exercise Duration: While sweat rate is per hour, the total volume of sweat lost is directly proportional to how long you run. Longer runs mean greater cumulative fluid loss.

- Environmental Conditions: The weather plays a massive role:

- Ambient Temperature: Hotter air reduces passive heat loss and increases reliance on evaporative cooling, driving sweat rates up.

- Relative Humidity: High humidity severely limits sweat evaporation. Your body might sweat more in humid heat trying to compensate, but much of it drips off uselessly, leading to inefficient fluid loss.

- Wind Speed (Air Velocity): A breeze enhances both convective heat loss and sweat evaporation, improving cooling efficiency and potentially reducing the required sweat rate compared to still air.

- Solar Radiation: Running in direct sunlight adds a significant heat load, forcing your body to sweat more than running in the shade or at night.

- Clothing and Equipment: What you wear matters immensely. Heavy, dark, non-breathable, or multiple layers trap heat and moisture, impairing cooling and forcing higher sweat rates. Think of American football players in full pads – they exhibit extremely high sweat rates.

C. Adaptive Factors: Your Body Learns!

- Heat Acclimation: If you repeatedly train in hot conditions, your body adapts over 8-14 days to handle the heat better. This process, called heat acclimation, involves several key changes related to sweating:

- Earlier Onset of Sweating: You start cooling sooner.

- Increased Sweat Rate Capacity: Your sweat glands become capable of producing more sweat per hour (sometimes up to threefold!), offering greater potential for evaporative cooling.

- More Dilute Sweat (Sodium Conservation): This is a crucial adaptation. Your body becomes better at reabsorbing sodium as sweat travels through the duct, resulting in sweat that has a lower concentration of sodium (and chloride) than when you were unacclimatized. This helps conserve precious electrolytes. This adaptation often happens relatively quickly, within the first week of heat exposure.

- The Acclimation Hydration Paradox: Here’s the important takeaway for your hydration plan: While heat acclimation makes your sweat more dilute (less salty), it also increases your maximum sweat rate. This means an acclimatized runner exercising in the heat will likely lose a greater total volume of fluid per hour compared to their unacclimatized state under the same conditions. Therefore, your hourly fluid replacement needs will likely be higher after acclimatization, even though each liter of sweat contains less sodium. Your hydration plan needs to adjust for both increased volume and altered concentration!

(Imagine a summary table here listing Factor, Effect on Sweat Rate, Explanation)

IX. Decoding the Numbers: Interpreting Your Sweat Rate Data

Okay, you’ve crunched the numbers using the calculate sweat rate running formula. What does your result actually mean?

A. What Are “Normal” Sweat Rate Values?

Sweat rates vary wildly, but understanding typical ranges provides context:

- Common Range: Most recreational and elite athletes fall somewhere between 0.5 Liters/hour and 2.0 Liters/hour (approx. 17 to 68 oz/hr) during exercise.

- Extremes Exist: Rates below 0.5 L/hr or significantly above 2.0 L/hr are possible. Rates exceeding 3.0 L/hr (101 oz/hr) have been recorded, especially in large, acclimatized athletes exercising intensely in the heat. Some outliers are even higher.

- Practical Benchmarks (General Guide):

- Low: < 1.0 L/hr (< 34 oz/hr)

- Moderate/Average: 1.0 to 1.5 L/hr (34 to 51 oz/hr)

- High: 1.5 to 2.5 L/hr (51 to 85 oz/hr)

- Very High: > 2.5 L/hr (> 85 oz/hr)

- Sport Differences: Average rates can vary by sport due to typical intensity, duration, environment, and gear (e.g., endurance athletes often average around 1.2-1.3 L/hr, while American football players average higher due to equipment).

- Size Matters: Always interpret your sweat rate relative to your body size. A 1.5 L/hr rate might be very high for a petite runner but only moderate for a large athlete.

B. Context is King: Why One Measurement Isn’t Enough

A single sweat rate test gives you a snapshot under one specific set of conditions. As we saw in Section VIII, your sweat rate changes drastically based on intensity, temperature, humidity, clothing, and more. A value from an easy, cool-weather run tells you little about your needs during a hot, humid race.

Create Your Personal Sweat Map:

To truly understand your fluid losses, you need to perform sweat rate testing multiple times across a range of conditions relevant to your training and racing:

- Vary Intensity: Test during easy runs, tempo runs, and interval sessions.

- Vary Conditions: Test in different temperatures (cool, mild, hot) and humidity levels (low, moderate, high).

- Vary Clothing: Test with the different outfits you typically wear in those conditions.

By collecting data across these variables, you build a personal sweat rate profile or ‘map’. This provides a much more robust foundation for predicting fluid needs and planning hydration for different scenarios, moving beyond a single, potentially misleading number.

X. The Salty Side of Sweat: Understanding Sodium Loss

Quantifying your sweat rate tells you how much volume you’re losing, but that’s only half the hydration equation. Remember, sweat contains electrolytes, and the most significant one by far is sodium (Na+).

- Sweat Isn’t Just Water: It’s a saline solution. Sodium plays vital roles in nerve function, muscle contraction, and fluid balance.

- Massive Individual Variation in Sweat Sodium Concentration ([Na+]): This is where things get really personal. The amount of sodium in sweat varies enormously between individuals – far more than sweat rate itself. Reported ranges span from less than 200 mg of sodium per liter of sweat (<10 mmol/L) to well over 2,300 mg/L (>90-100 mmol/L)! While averages are often cited, relying on them is highly unreliable. You could be a “salty sweater” or lose very little sodium.

- Factors Affecting Sweat [Na+]: While more genetically determined and stable than sweat rate, sweat sodium concentration can be influenced by:

- Sweat Flow Rate: Generally, higher sweat rates lead to higher sodium concentration (less time for reabsorption).

- Dietary Sodium (Long-Term): Habitual intake can influence it over time.

- Heat Acclimation: Significantly reduces sweat sodium concentration (more dilute sweat).

- Calculating Total Sodium Loss: If you know both your sweat rate and your sweat sodium concentration, you can calculate your total sodium loss:

Total Sodium Loss (mg) = Sweat Rate (L/hr) * Sweat [Na+] (mg/L) * Exercise Duration (hr) - Measuring/Estimating Sweat [Na+]:

- Accurate Measurement: This typically requires specific lab or field testing methods involving absorbent patches, whole-body washdown techniques, or specialized devices that measure conductivity.

- Subjective Signs: Noticing white, crusty salt stains on your skin or clothes after a run, or sweat stinging your eyes or tasting distinctly salty, suggests you might be a saltier sweater. However, these are highly qualitative and cannot provide a precise number for planning.

- Why Sodium Loss Matters: Significant sodium depletion can impair nerve and muscle function, contribute to muscle cramps (though the link is complex), hinder fluid retention, and critically, increase the risk of hyponatremia if large volumes of plain water are consumed.

- The Complete Picture: A comprehensive hydration strategy must consider both the volume of fluid lost (guided by sweat rate) and the amount of sodium lost (guided by sweat rate and sweat [Na+]). Calculating sweat rate alone only addresses the volume part.

XI. Turning Data into Action: Building Your Personalized Running Hydration Plan

Armed with knowledge about your sweat rate (ideally across various conditions) and potentially an estimate or measurement of your sweat sodium concentration, you can finally ditch generic advice and build a plan tailored to you.

A. Translating Sweat Rate into Fluid Needs:

- 1. Pre-Hydration (Start Hydrated!):

- Goal: Begin every run in a state of euhydration (normal body water balance).

- General Guideline: Aim to drink about 500 ml (17 oz) of fluid 2-3 hours before exercise, allowing time for absorption and voiding excess. An additional 200-300 ml (7-10 oz) 10-20 minutes pre-run can also be beneficial. Adjust based on anticipated losses and tolerance.

- 2. During Exercise (The Main Event):

- Primary Goal: Prevent excessive dehydration – generally aim to keep body weight loss below 2% of your starting weight.

- Use Your Sweat Rate: Your calculated sweat rate (for the specific conditions) is your starting point for estimating hourly fluid needs. If you sweat 1.2 L/hr in the heat, that’s your benchmark.

- The “Replace 100%” Debate: Replacing every drop lost is often impractical (limits on absorption, carrying capacity), can increase gut issues, and may raise hyponatremia risk if sodium isn’t adequate. Mild dehydration (<2%) might be tolerable, especially in cooler conditions or shorter runs.

- Modern Strategies:

- Target a Percentage: Aim to replace a significant portion (e.g., 60-80%) of your predicted sweat loss.

- Drink to Thirst: Listening to your body’s thirst cues can work well for many, especially during lower intensity or shorter runs in mild weather. However, thirst can lag behind actual needs during high intensity, in heat, or for very high sweat rates.

- Consume Max Tolerated Amount: Drink as much as you comfortably can without causing stomach upset, up to your sweat rate.

- Individualize: The best approach uses your sweat rate data to set a realistic target intake range for specific conditions. Refine this target based on practical experience during training, considering gut comfort, perceived thirst, weather, and monitoring weight changes on longer runs. Find a sustainable rate that minimizes dehydration (<2% loss) without causing discomfort or overhydration.

- 3. Post-Exercise Rehydration (Recovery Fuel):

- Goal: Fully restore fluid balance, especially important if training again soon.

- How Much: Aim to consume 125-150% of the body weight lost during the run. Example: Lost 1 kg (≈1 L or 34 oz)? Drink 1.25-1.5 L (≈42-51 oz).

- Why More? You need extra to compensate for continued urine production during the rehydration period.

- Timing: Ideally consume this within the first 2-6 hours post-exercise.

B. Addressing Electrolyte Replacement (Focus on Sodium):

Fluid alone isn’t enough for longer runs, hot conditions, or if you’re a salty sweater. Replacing lost sodium is crucial for:

- Maintaining blood volume and osmolarity (helps retain fluid).

- Supporting nerve and muscle function.

- Potentially reducing cramp risk (anecdotal evidence is strong).

- Mitigating hyponatremia risk.

Recommendations:

- During Exercise: For runs > 1-2 hours, runs in the heat, or if you have high sweat rates/high sweat sodium loss, your fluids should contain sodium.

- If [Na+] Unknown: Standard sports drinks (typically 300-700 mg sodium per liter or ~15-30 mmol/L) are a reasonable starting point. (ACSM previously suggested 500-700 mg/L for exercise >1 hour).

- High Losses/Salty Sweaters: May need higher sodium concentrations or supplemental electrolyte capsules/tabs. Personalization via testing or careful trial-and-error is key.

- Post-Exercise: Consuming fluids and foods containing sodium after exercise enhances rehydration and speeds electrolyte balance restoration compared to plain water. Salty snacks or electrolyte recovery drinks can be beneficial.

C. Putting It All Together: Your Actionable Hydration Plan:

- Build Your Profile: Use data from multiple sweat rate tests to estimate your fluid (and potentially sodium) loss rates for different anticipated conditions (e.g., easy cool run, tempo hot run, race pace moderate run).

- Set Targets: Based on the estimated losses for a given scenario, set a target hourly fluid intake range (aiming to replace 60-80% of losses, stay <2% BW loss) and sodium intake target (mg/hr, if applicable).

- Choose Your Weapons: Decide on your fluid/electrolyte sources (water, specific sports drinks, electrolyte tabs/capsules).

- Plan Logistics: How will you carry fluids (bottles, vest)? How often can you access them (aid stations)? Plan your intake frequency and volume based on accessibility (e.g., “Drink 6 oz every 15 minutes” or “Drink X amount at each aid station”).

- PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE! This is non-negotiable. Test your entire hydration strategy (fluids, electrolytes, timing, logistics) during training runs that mimic race conditions. Assess gut tolerance, refine timing, and confirm effectiveness.

- Consider a Planning Worksheet: Create a simple sheet to track your plans for different conditions:

- Pre-Run Plan (Timing, Fluid, Amount)

- During-Run Plan (Columns for different conditions: Intensity/Temp/Humidity)

- Rows for: Estimated Sweat Rate, Target Fluid Intake, Target Sodium Intake, Fluid Choice, Practical Plan (e.g., X oz every Y mins).

- Post-Run Plan (Target intake based on weight loss, Fluid type)

- Notes Section (Record tolerance, effectiveness, adjustments).

This systematic approach, grounded in your individual data but refined through practice, is how you truly optimize hydration.

XII. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Do I need to calculate my sweat rate after every run?

- No. The goal is to test across a range of conditions (intensity, weather, clothing) relevant to your training and racing to build your personal profile. Once you have a good map, you only need to re-test occasionally or if conditions change significantly (e.g., moving to a new climate, major fitness change).

- Is drinking plain water enough?

- For shorter runs (under 60-90 mins) in mild conditions, often yes. For longer runs, intense efforts, hot/humid weather, or if you have high sweat/sodium losses, water alone is usually insufficient. You’ll need electrolytes, primarily sodium.

- How can I tell if I’m a “salty sweater” without a test?

- Visible white, crusty salt stains on your skin or dark clothing after exercise, sweat that stings your eyes badly, or tastes very salty are clues. However, these are subjective. A test is the only way to know your actual sweat sodium concentration for precise planning.

- Are online sweat rate calculators reliable?

- Yes, if you input accurate measurement data (weight, fluid intake, urine, duration). They simply automate the calculate sweat rate running formula. The accuracy depends entirely on your input quality.

- Are there risks to drinking too much water?

- Yes. Drinking excessive amounts of plain water, especially during prolonged exercise when you’re also losing sodium through sweat, can lead to Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia (dangerously low blood sodium levels), which can be serious or even fatal.

- If I get muscle cramps, do I just need more sodium?

- Maybe, but it’s complex. While electrolyte imbalances (including sodium depletion) are often implicated in exercise-associated muscle cramps, fatigue, dehydration, and neuromuscular factors also play significant roles. Addressing sodium intake is one part of the puzzle, but not always the sole cause or solution.

XIII. Conclusion: Integrate Sweat Rate Knowledge into Your Running Routine

Understanding and applying your personal sweat rate data is a powerful tool for any runner serious about performance, health, and enjoyment.

We’ve covered the science of sweating, the detrimental effects of dehydration, the practical steps of using the calculate sweat rate running formula, the myriad factors influencing your losses, and the critical importance of sodium.

The real value lies in moving beyond generic hydration advice. By understanding your unique physiology, you can build targeted strategies to:

- Optimize body temperature regulation.

- Prevent performance-killing dehydration (>2% body weight loss).

- Reduce the risk of heat illness.

- Minimize the risk of hyponatremia through appropriate fluid and electrolyte intake.

- Ultimately, run stronger, feel better, and recover faster.

Your Action Plan:

- Test Regularly: Conduct sweat rate measurements under various conditions relevant to your training and racing goals. Build your personal sweat map.

- Consider Sodium: If you run long distances, train/race in the heat, or suspect you’re a salty sweater, get an estimate or measurement of your sweat sodium concentration to refine your electrolyte plan.

- Develop & Practice: Use your data to create specific hydration plans for different scenarios. Meticulously practice these plans in training.

- Monitor & Adjust: Pay attention to your body (thirst, urine color, morning weight) and be ready to tweak your plan based on conditions, acclimation status, and how you feel.

Stop guessing with your hydration. Take the time to understand your individual needs using the calculate sweat rate running formula and the principles outlined here. It’s an investment that will pay dividends in every stride you take. Happy (and well-hydrated) running!

About the Author

Lost Pace is an ultramarathon runner, shoe-tester and the founder of umit.net. Based year-round in Türkiye’s rugged Kaçkar Mountains, he has logged 10,000 + km of technical trail running and completed multiple 50 K–100 K ultras.

Blending mountain grit with data, Lost analyses power (CP 300 W), HRV and nutrition to craft evidence-backed training plans. He has co-written 260 + long-form guides on footwear science, recovery and endurance nutrition, and is a regular beta-tester of AI-driven coaching tools.

When he isn’t chasing PRs or testing midsoles, you’ll find him sharing peer-reviewed research in plain English to help runners train smarter, stay healthier and finish stronger.

Ultrarunner · Data geek · Vegan athlete